What It Actually Takes to Get a Sexual Assault Conviction

Everyone is talking about sexual assault these days. Although this heightened awareness is making feminists and activists rejoice, it has also highlighted the areas needed for growth.

Almost every time I have gotten into a conversation about sexual assault, be it in the classroom or over happy hour, the topic of false reporting comes up. Someone wants to mention that “they knew someone who knew someone whose life was almost ruined because a crazy girl made up getting raped.”

If someone is sent to jail or punished for a crime that they did not commit, it is a grave injustice and a complete failure of our legal system. That should be taken very seriously. I am not here to belittle those instances, or to disregard the significant and gross impact that would have on someone’s life.

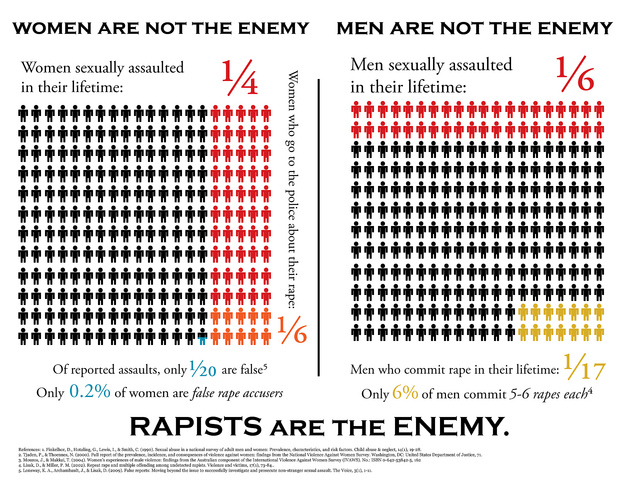

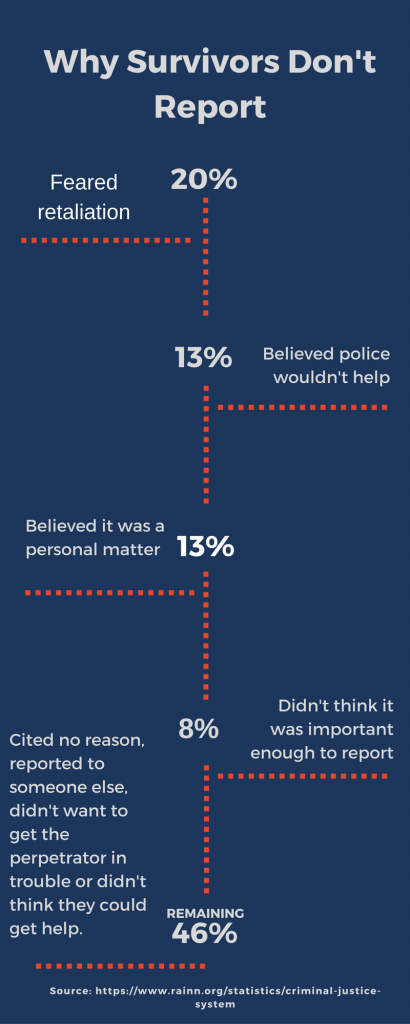

However, it is important to realize that false reporting is essentially a rape myth, which has little basis for belonging in these conversations. In reality, only about 1 out of three sexual assault’s are even reported. So, for every 1,000 people who report, 2,000 more remain silent. For men, the discrepancy of not reporting is most likely higher, since they suffer from the additional stigma that sexual assault is a women’s issue; lessening their chances of being believed and supported if they came forward.

If you think that filing a false sexual assault report is easy to do, then it is important to know what it really takes to file a report in the first place. If you are sexually assaulted, you must get a rape kit done. This is one of the few ways of documenting evidence, so it is crucial, if survivors want an actual chance at legal justice, to get a rape kit. Due to the nature of the crime, documenting evidence is a time sensitive, invasive and lengthy procedure. Survivors only have 120 hours to get one done, and are told not to shower, drink water, eat, brush their teeth, or change out of the clothes they were assaulted in, which will most likely be confiscated for further evidence, prior to.

People might question who the suspect is in any other crime, but they don’t question that the crime itself actually took place; which is what we frequently do when someone is sexually assaulted.

After that, you have to file a police report. You will be asked to explain in great detail just how this was a sexual assault, and that experience will vary depending on how well trained your police officer is. Afterwards, you will wait, for a long time, to see if your case will even be considered for court. Often times it won’t be, because the burden of proof is so high, and the ability to collect evidence is so limited, it prevents many survivors from getting the chance at ever prosecuting their crimes.

If your case is accepted and makes it to trial, it is still judged by a jury made up of people who have been raised in the same culture as you and I. They are supposed to impartially decide whether or not the perpetrator should get locked away. Sometimes juries think the sentence is too grave a punishment for the perpetrator, deeming the sexual assault a “mistake” instead of a crime. Even the judge might agree, like in the case of Brock Turner, and then, despite the evidence and testimony, they might still get away scot free or without a felony offense. When these things happen, we cannot ignore the fact that not taking sexual assault seriously impacts our society.

How the Idea of False Reporting Prevents Survivors from Coming Forward and Receiving Justice

If a survivor chooses to report, they will have much more than the legal battle to deal with. Survivors who bravely choose to come forward often face devestating social consequences. Throughout the whole process, which might take over a year, the survivor is being questioned by everyone she knows and loves.

Th ey will constantly be asked whether they are sure this really happened, that it just wasn’t a misunderstanding. These questions might be well meaning, but they only contribute to the horrific experience they are going through. They might be ostracized by their peers or friends, particularly if the perpetrator is a friend or partner, which is true in most cases.

ey will constantly be asked whether they are sure this really happened, that it just wasn’t a misunderstanding. These questions might be well meaning, but they only contribute to the horrific experience they are going through. They might be ostracized by their peers or friends, particularly if the perpetrator is a friend or partner, which is true in most cases.

They might suffer from PTSD, fall into a depression or battle anxiety, making it impossible for them to complete their daily responsibilities. It’s not uncommon that one might take a leave of absence from school, have to quit their job, or go on medication or to therapy.

We are shown time and again that society deeply punishes survivors for coming forward, and that punishment can continue for years afterwards.

Why do we have such a hard time stomaching that sexual assault survivors are telling the truth?

If we take all those facts into consideration, and it’s still hard to believe that it’s unlikely for someone to go through the trouble of crying rape, just look at the chances of their perpetrators getting convicted. If you wanted to punish someone by falsely accusing them of a crime, sexual assault would be an incredibly poor choice. The chances of conviction are so small that a false report would have great difficultly even making it to court.

This is not to say that false reporting doesn’t exist, somewhere. But they are comparable, if not less than, the chances of false reporting for any other crime. Yet those crimes are never debated in the same way that sexual assaults are, which is the key difference here.

People do not automatically assume you are lying when you say that someone robbed you. People do not ostracize you, bully you, or ask if you are really sure that that’s what the robber was doing when he held you at knifepoint and stole your wallet. People might question who the suspect is in any other crime, but they don’t question that the crime itself actually took place; which is what we frequently do when someone is sexually assaulted.

So why do we have such a hard time stomaching that sexual assault survivors are telling the truth? Why are we afraid that someone might be making this up? Why do we worry more about the slight possibility of charging an innocent man, than worrying about the greater possibility of letting a rapist walk free? Why do we value the perpetrators’ freedom over the survivors?

Next time you have doubts about a sexual assault report, I invite you to to take a moment to really think about why it is that disbelief might be your first reaction, and where that assumption is coming from.